|

A CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION! |

|

|

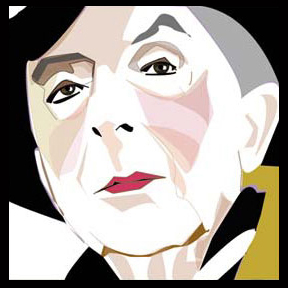

THE QUENTIN CRISP ARCHIVES

PHILLIP WARD

Friend and confidant

While watching The Naked Civil Servant in 1975, never did I realize or even imagine the significance or importance Quentin Crisp would be in my life. Never! My mother and a few siblings were gathered about the living room watching television. Bored with game shows, Mother stood and moved toward the television set to turn the dial. This was a time when turn-dial television was the standard mode of operation, rather than the remote control as we have it now. She stopped at the local public television station where a movie had just begun. It was The Naked Civil Servant, and “the” Quentin Crisp was introducing the movie with teacup in hand addressing the viewers. Mother left the dial on that station and returned to the sofa to watch the movie. While watching The Naked Civil Servant in 1975, never did I realize or even imagine the significance or importance Quentin Crisp would be in my life. Never! My mother and a few siblings were gathered about the living room watching television. Bored with game shows, Mother stood and moved toward the television set to turn the dial. This was a time when turn-dial television was the standard mode of operation, rather than the remote control as we have it now. She stopped at the local public television station where a movie had just begun. It was The Naked Civil Servant, and “the” Quentin Crisp was introducing the movie with teacup in hand addressing the viewers. Mother left the dial on that station and returned to the sofa to watch the movie.My stomach wrenched in fear that others in the room would see the delight in my eyes while watching this man’s life unfold on the screen. It was as though he was addressing me directly. It was a directive to be one’s self at all cost. “Be” was the answer to life’s experience and adventure. Meanwhile my family were all laughing and offering bigoted jokes and anti-homosexual commentary. Little did they know that they were also directing the same sentiments toward me. Mother never switched the channel, though, and we watched the movie to the very end. That night while lying in bed and staring at the floral-printed wallpaper and darkened ceiling in firelight, I pondered what it all meant, the movie and this gentle man’s life. How did it relate to me? I was nothing like him. His effeminacy was not my character, but the fear of being discovered and harassed was a constant concern. Emotions stirred within and goaded me toward the public library to learn more about Quentin Crisp and to read his autobiography. I needed to learn more about homosexuality, because homosexual was what I was. I needed to understand it all, and to not live in fear for being gay. Then I discovered the World! There were others like me and Quentin Crisp was my introduction. After college in 1979, I moved to Manhattan, where I have lived these past thirty years. In February 1986, I met the “live and in person” Quentin Crisp. My secretary, Kathy Hurt met him while standing in line at the East Village post office during her lunch hour and engaged him in conversation. I goaded Kathy to call him, as he was listed in the phone directory, and set up a date for dinner. I would come along! And, consequently, I was overwhelmed by his generosity of spirit and kindness—and with his honesty of heart. And despite his spoken adversity toward love and being loved, Quentin exuded unconditional love to those he trusted and believed in. Because of this and over the years that followed, I enjoyed an intimate and close friendship with Quentin Crisp, and one which I cherish daily. During the last two years of his life, Quentin and I worked on the manuscript of his last book, The Dusty Answers. It was recorded on audiotape in his room on East Third Street and at my apartment on Christopher Street. Regularly, I would visit him, bringing him food and supplies, and always delivering his mail from the lobby’s counter where the postman deposited mail for the whole building. We would begin our sessions with conversation about our day, and Quentin would open his mail while quickly deciding which ones required his reply. We shared sandwiches and pastries and drank “kinky” water (seltzer). Sometimes Quentin would boil potatoes for dinner and we would eat from the pot, while sipping scotch and enjoying fantastic conversation. Quentin would either sit on the side of the bed or stretch out on it, resting comfortably as though he were visiting a psychiatrist’s couch. And always with a smile, he would say, “Where shall we begin?” He was excited about doing this new book, but doubted he would be alive to see it printed. Quentin was bringing closure to his life and wanted to have the last word on it. He was hurriedly energetic and challenged his “failing” body daily. In July 1999, Quentin finished the “official” recordings for The Dusty Answers, however we continued recording our sessions together. These moments became more an ongoing conversation, or an assessment of the full picture of which was his life. As a friend and editor of The Dusty Answers, I was provided an overwhelming sense of respect and responsibility, a period of focus and concentration, and an enormous thank-you to Quentin for allowing me to be part of his life. Quentin’s health began to decline in the winter of 1998-99, while performing on 42nd Street at The Intar Theatre under the direction of John Glines. This was Mr. Crisp’s last run in New York City of his one-man show, An Evening with Quentin Crisp. It opened on his 90th birthday and closed on January 31, 1999. During this time, Quentin became ill and probably had pneumonia, but most definitely the flu. Still, he struggled getting to the theatre on time by taking a bus up Third Avenue and then across 42nd Street to the theatre, despite a taxi allowance given him by the producer. “Money is for saving, not for spending.” He was determined not to fail or to disappoint Mr. Glines and the theatergoers who paid money to come see him. Quentin never missed a performance, despite his ill health. Immediately following the run at The Intar and between all his appearances and lunches and dinners already scheduled in his “Sacred Book” (his daily planner), we continued our sessions. Nearing the end of July, though, Quentin began tidying up his room, creating a small path for one to go from here to there. And anyone who knows anything about Quentin Crisp, it was unlike him to clean any part or rearrange anything in his room. He did not do it and did not allow others to do so either. However, he wanted to prepare his room for the people who would visit it after his death. By summer’s end, Quentin’s room met his approval. It was navigable and tidy. And he was happy that we had arranged the closet so that all his legal documents and estate papers would be easily found. He had great concern about such matters, especially his Last Will and Testament. Quentin wanted all his affairs in order and that is what we had done. Quentin’s tour of England with Authors on Tour (Charles Lago and Chip Snell) had been unexpectedly canceled by a directive not his own. And despite the fury raging inside him, Quentin kept an outward calm repose. He had lived a long and determined life of his own accord, for and by himself, and how is it now that he should live it for or determined by another person’s worried concern. I quieted his worry by assuring him that I had nothing to do with the situation and that I supported any wish he desired. Quentin immediately set the tour back in motion and began to focus on his November trip to Manchester. He made a decision to go, knowing well that his health may even fail him along the way there. I reminded Quentin that there would be significant stress on his already weak heart; especially with the two air-pressured flights he would take to arrive there. He was pleased and felt it might be a “significant death”. He was happy to be going and did not care where he died, whether it be in England or in New York. “In my present condition, I look forward to being extinct.” The night before his departure, Quentin joined Charles Barron and me for dinner at Haveli, an Indian restaurant on Second Avenue and only a few blocks north from Cooper Square Diner. He had Tandoori chicken for dinner, sipped scotch and water, ate dessert and drank coffee while continuing our on-going conversation about his life and it’s coming end. But earlier in the evening at his apartment, he seemed agitated for some reason. I was unsure why, though I suspected Quentin was not taking the heart medicine I had delivered to him only a couple days before. I wanted to make sure he had all his medicines and toiletries before leaving on his trip. As for the heart pills, though, he felt why take them, especially if they were to prolong his life when he only wanted to die. Charles and I walked Quentin back to 46 East Third Street. I sensed it was our last walk together, with him holding onto my arm while slowing walking down Second Avenue toward his building. I escorted him inside, and we quickly spoke before hugging one another farewell. I kissed Quentin on his cheek and said, “Have a safe trip, sweetheart. Hurry back home! I love you, Quentin.” And he said, “Thank you. You are very kind. And I love you too. Goodbye.” I stood at the bottom of the stairs and watched him climb the first flight, huffing and puffing, with his right hand grasping the railing to help pull himself up the stairs. I remained in the lobby listening to him continue to his floor. His grunts and sighs still sing inside my head remembering him that night. Intuitively, I felt this was the last time I would see Quentin. He was not coming back alive. A deep pang struck my heart as I left his building. Sorrow enveloped me. Charles and I were quiet on our way home. We sensed the same sadness, the same truth. I called Quentin the following morning wishing him well and much success with the tour, and a wish for him to hurry back home. He was eager to leave, though, especially knowing the possibilities of what the flights might do to his heart. Quentin embraced the chance! His life was in order, with all corners tidied, and the discarded in the trash heap. He was ready and prepared to die, and off to England he went. From The Dusty Answers, Quentin writes, “I have kept my optimism going so far by coming to America. But now my optimism is dwindling and I long for death, which most people would consider was pessimistic, though I do not think so. I shall like being dead. At least I shall enjoy dying. When I’m dead, of course, I shall have no opinions about anything. . . . And I can’t afford to believe in life after death. The nicest thing you can say about life is that it will end. The idea of falling out of your mother’s womb with the words, ‘Here again!’ is too much for me to bear. . . . I'm not afraid of dying. So, a heart attack would do fine. That would be dying in style.” Quentin’s first evening in England became his last. He and Chip arrived in Manchester safely and enjoyed an evening visiting with his hostess before heading off to his room for sleep. On the morning of November 21, 1999, Chip found Quentin lying on his bed lifeless, and with nitro pills clutched in his hand. He had died in style by having a heart attack during the night. And Quentin died alone, which was one of his greatest desires. Following Quentin’s passing, I created The Quentin Crisp Archives from personal effects left me in his Will. It is QCA’s mission “to preserve and maintain the manuscripts, letters, recordings, artwork by and about, and various artifacts and ephemera related to the life and legend of Quentin Crisp, and to promote his philosophy of individuality, self-acceptance, and tolerance.” Quentin provided us, the world at large, gay and straight, a simple philosophy of happiness and being. He was an atheist, yet his Buddhistic and existentialistic instructions offer an insight into the man he was while providing an insight into who and what we are to ourselves and to others. I encourage everyone to read Quentin Crisp’s works and to hear him on recordings. His philosophy will have some sort of impact on you, whether you invite it or not. And with this in mind, we now begin a year of celebration honoring Quentin Crisp with the new biopic, An Englishman in New York, written by Brian Fillis and starring John Hurt as Mr. Crisp in New York City during the 80s and 90s. The movie made its world premiere at The Berlin International Film Festival's Panaroma on February 11, 2009. The film made its English debut at the 23rd London Lesbian & Gay Film Festival on March 26th. Also shown was Uncle Denis?, a film by Quentin's great-nephew Adrian Goycoolea! An Englishman in New York premiered in New York on April 27, 2009 at the Tribeca Film Festival, and is scheduled to show on American and British television later in Fall 2009. His purple fedora was on display in the exhibit “Hats: An Anthology by Stephen Jones” at England’s Victoria and Albert Museum from February through May 2009. Quentin’s final book, The Dusty Answers, will be published for the very first time, hopefully, in the coming year. And this November 21st, we commemorate the 10th anniversary of Mr. Crisp’s death. All this makes for a great year to celebrate the life and legend of Quentin Crisp!  So, for over thirty years now have I known about Quentin Crisp—through his writings and with knowing the man personally. I listened to his wisdom, as he was a mentor and a friend. He listened as well and, with that, I learned how to “be” with calm ease. There is no more fear of being discovered or harassed by threatening forces or other forms of hostility. And with this considered, I am a better human for having known Quentin Crisp. And as with Quentin’s gift to me as his friend, I offer The Quentin Crisp Archives to the world at large as a giant thank-you to Quentin on his centenary. So, for over thirty years now have I known about Quentin Crisp—through his writings and with knowing the man personally. I listened to his wisdom, as he was a mentor and a friend. He listened as well and, with that, I learned how to “be” with calm ease. There is no more fear of being discovered or harassed by threatening forces or other forms of hostility. And with this considered, I am a better human for having known Quentin Crisp. And as with Quentin’s gift to me as his friend, I offer The Quentin Crisp Archives to the world at large as a giant thank-you to Quentin on his centenary.Happy 100th, Sweetheart! |

|

Read what Phillip Ward wrote for the tribute booklet An Evening for Quentin Crisp: The Memorial. < |

Photograph copyright © by Phillip Ward. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Photograph of Mr. Ward with Quentin Crisp by Jim Tamulis.

Photograph copyright © by Phillip Ward. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Site Copyright © 1999–2009 by the Quentin Crisp Archives.

All rights reserved.