|

|

QUENTIN THE MODEL

by Vic Stevens |

|

[This article is reproduced from the Spring 2000 issue of Bare Facts magazine. Some readers had expressed surprise at the publicity following the death of London’s best-known model of the 20th century. It was not only the discovery that he had a huge following outside of the art scene, but the fact that his modeling career was hardly mentioned that seemed so strange to those who knew him in the days before The Naked Civil Servant. Vic Stevens tries to redress the balance by taking a look at his reputation as a model.] |

|

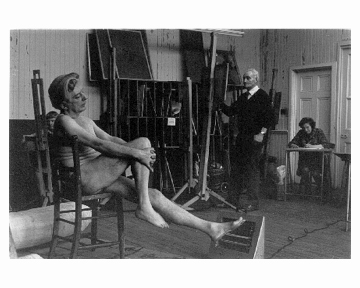

The death of Quentin Crisp in November 1999 at the age of ninety was treated in Europe and America as a major item of news. He was variously described by the media as a writer, a celebrity, and gay rights activist.

The last of these three tags is probably quite wrong, since the basis of Quentin’s philosophy seemed to be that we are all engaged in a daily struggle to deserve anything at all, and no one is issued with a set of rights at birth. His behavior and appearance—which were extraordinary for the 1940s and 1950s and quite intolerable to the vast majority of people in those days (he was beaten up a few times in London)—owed much more to his great need to be himself than to any crusade on behalf of others.  A writer and celebrity he undoubtedly was, with a string of book titles to his name. His first book, Lettering for Brush and Pen, was published in 1936. But what finally propelled him out of the London life modeling scene was the publication of The Naked Civil Servant in the 1960s. It helped that the excellent John Hurt played Quentin in the film version of the book. Quentin was on to a winner with the title alone, a fact recognized even before the book was published by his friend Miss [Margaret] Vanek. A writer and celebrity he undoubtedly was, with a string of book titles to his name. His first book, Lettering for Brush and Pen, was published in 1936. But what finally propelled him out of the London life modeling scene was the publication of The Naked Civil Servant in the 1960s. It helped that the excellent John Hurt played Quentin in the film version of the book. Quentin was on to a winner with the title alone, a fact recognized even before the book was published by his friend Miss [Margaret] Vanek.Of course, the name Vanek brings us to the significance of the Quentin Crisp story to Bare Facts readers. She and Quentin were life models during the same period, lasting some twenty-five years, and she eventually became responsible for booking the models for most of the life classes in the adult education centers of London and the Home Counties. In other words, whereas the media reports and Web sites are concerned with the post-Naked Civil Servant, the post-modeling Quentin Crisp who had already acquired an international following as an inspirational rebel (and guru to some), in Bare Facts spheres you only hear and have only ever heard of Quentin the Model. Sometimes it seems that there is almost no one in the London life art scene over fifty who has not either drawn Quentin Crisp or posed with him. It is clear, both from the pages of The Naked Civil Servant and from personal memories of him, that having turned to life modeling because it was the only work anyone would give him (which is by no means an unusual introduction to the profession), he never lost his contempt for most of the students and tutors; yet he quickly set about making the most of the job, wo  rking hard to develop what he called his ‘aesthetic’ style of posing. rking hard to develop what he called his ‘aesthetic’ style of posing.He tried desperately to be a performer for them, and in this idea of modeling as performance art in its own right he was in general a long way ahead of his time, though not alone. His poses and philosophy of posing, as well as his whole manner in the life room, might have gone down better these days—though certainly not everywhere. Nostalgia and Quentin’s fame in later life have turned him into the Life Model of the 20th Century in the folklore of British life art. Yet when you press individuals for specific memories, there is a curious disharmony between general reputation and particular comments. What, for example, made Quentin such a good model? "Oh," enthuses one female tutor who drew him as a student, "he had such a lovely little bottom. It was all I ever wanted to draw." Another says, "Well, he did these amazing poses," but then adds, "Mind you, he used to overreach himself. The tutor became very angry one day and said ‘Now look here, Mr. Crisp, instead of shaking like a pneumatic drill, why don’t you do poses that you can hold and we can draw?’"  Understandably for the times, Quentin’s appearance and manner sometimes distracted people from their work. A tutor, who was a student at Beckenham School of Art when he was booked to pose there, says, "Can you imagine the reactions of a naïve girl of sixteen in the 1950s, already nervous about encountering her first male model, suddenly being confronted by this apparition with bright orange hair and a sequined posing pouch? I froze rigid. I couldn’t even begin to draw." A man of friendly, easy-going disposition who is still working as a model told me, "I soon found out you couldn’t sit down and have a nice chat with him. He was only interested in cutting you down with his wit." Several people even recall the  tension caused by Quentin’s insistence on going into the women’s lavatories in the colleges in order to put his make-up on. tension caused by Quentin’s insistence on going into the women’s lavatories in the colleges in order to put his make-up on.Some readers will say that my reporting of all these rather negative comments is a case of sour grapes. After all, male models in London can tire of the constant invocation of the name of Quentin Crisp. We are supposed to follow his example, but when we ask for details of exactly what it was he did and said, it begins to look as though we had better not follow it too closely—if we want to be booked again. Ironically, this is especially the case with some of those tutors from whose tongues the magic name rolls most readily. They have been known to refuse to accept certain very good male models from the Bare Facts model management service just because they are ever so slightly flamboyant. The fact remains that Quentin Crisp was one of the many life models throughout the ages who have had it in mind to elevate the work of the model to the point where it is a fully active component of the creative process. Soon after Quentin’s time as a model, there was a brief era when a significant number of tutors and students began to expect just that of models, but it seems to me we could be sliding back into the old, duller relationship. |

|

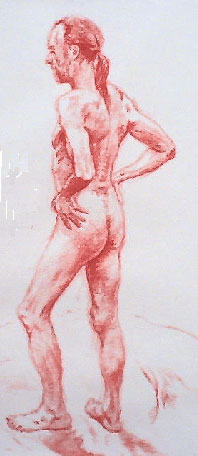

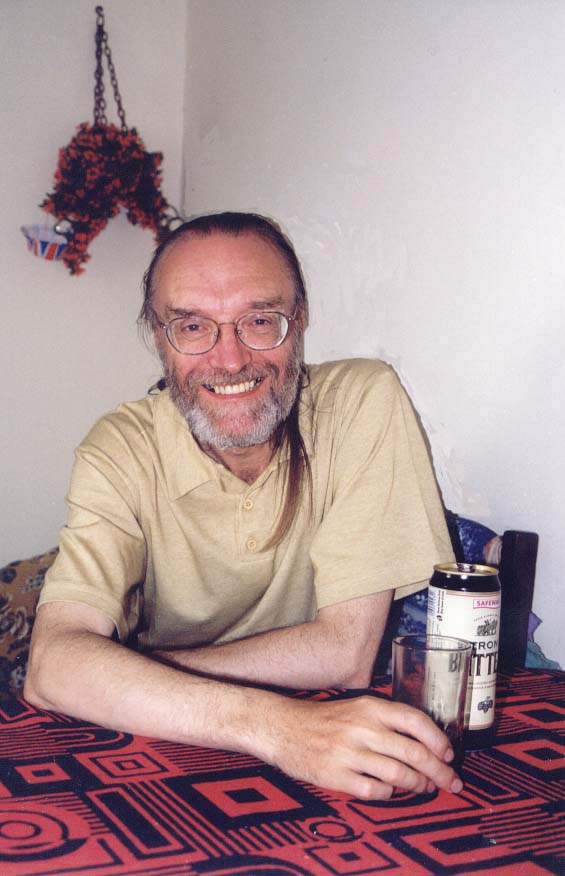

Quentin Crisp photograph © by Jean Harvey. All rights reserved. Used by permission Text and Vic Stevens photo copyright © by Vic Stevens and Bare Facts. Chalk drawing of Mr. Stevens by Simon Turvey at the Camden Sketch Club, circa 1998. All rights reserved. Used by permission.   Site Copyright © 1999–2008 by the Quentin Crisp Archives All rights reserved. |